RIYADH/LONDON: Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s recent assertion that the only way to resolve the Cyprus dispute is a two-state solution may have just muddied the waters further, rather than helping resolve Europe’s longest-running frozen conflict.

By rejecting the reunification of Cyprus under a two-zone federal umbrella, long favored by Greece and the UN, the Turkish leader has purposely raised the stakes in the run-up to a UN-led meeting to assess the possibility of resuming talks.

Erdogan’s comments also came shortly after the leaders of Greece and Cyprus said they would only accept a peace deal based on UN resolutions, rejecting the two-state formula supported by his government and the Turkish Cypriot leadership.

Greek Cypriots, who make up the EU member’s internationally recognized government, refuse to discuss proposals for a two-state union as it implies Turkish Cypriot sovereign authority.

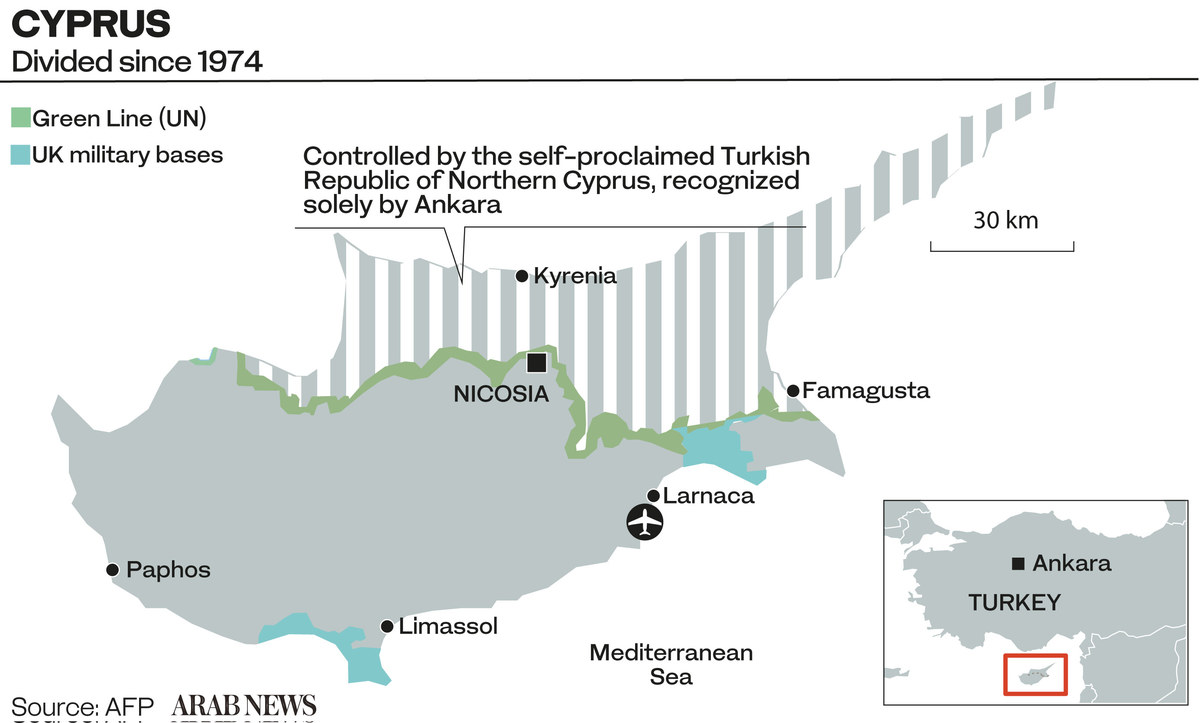

UN initiatives have failed to break the deadlock since the eastern Mediterranean island underwent a de-facto partition into Greek- and Turkish-speaking zones in 1974, when Turkey invaded and occupied its northern third in response to a coup in Nicosia engineered by the Greek junta.

The last UN-sponsored negotiations at the Swiss ski resort of Crans Montana came to naught in July 2017, going the way of the talks brokered by then UN chief Kofi Annan in 2004. For the March meeting, the UN is expected to invite Cyprus’ two communities as well as foreign ministers from the three guarantor nations – Greece, Turkey and Britain – to discuss how to move forward on the issue.

“Cyprus has been a quagmire for every UN secretary-general since the 1970s and (current UN Secretary-General Antonio) Guterres will be no exception,” Dimitris Tsarouhas, professor of international relations at Turkey’s Bilkent University, told Arab News.

“The parameters of a solution are known to all parties involved: a bi-zonal, bi-communal state that will incorporate international law provisions for the protection of the rights of all, and be functional enough to make it all work. Maximalist positions on both sides meant that golden opportunities were lost at Crans Montana in 2017 and during the Annan Plan in 2004.”

But then again, the rivalry runs deep. Greek Cypriots reject granting veto powers to Turkish Cypriots, and oppose both permanent troop presence and the continuation of military intervention rights by Turkey.

For its part, Turkey not only rejects suggestions of a federation between the two zones, it is also asking for hydrocarbon resources in the eastern Mediterranean to be shared. Last month, Greek and Turkish officials met in Istanbul after a five-year gap for exploratory talks on a raft of long-standing issues, including the status of Cyprus.

Conflicting claims to Cyprus’ political status and natural resources go back more than a century. Cyprus was annexed by Britain in 1914 at the conclusion of the First World War, following more than 300 years of Ottoman rule, and officially became a British colony in 1925.

Then, in the mid-1950s, Greek Cypriots launched a guerrilla war against British rule, demanding unification with Greece.

Independence was won in 1960 and a constitution agreed on by the island’s Greek and Turkish communities. Under the Treaty of Guarantee, the UK, Greece and Turkey each retained the right to intervene in Cypriot affairs, while Britain kept hold of two military bases.

Events moved quickly in 1974 when Greece’s military junta orchestrated a coup against Makarios in an attempt to annex Cyprus. The consequent deployment of Turkish troops on the island’s north effectively partitioned the island along the UN-policed Green Line.

While an estimated 165,000 Greek Cypriots fled south, about 45,000 Turkish Cypriots relocated to the north, where they established their own independent administration with Rauf Denktash as president. Despite a unanimous UN Security Council resolution, Turkey has refused to withdraw its troops from Cyprus.

Fresh attempts at UN-sponsored talks in the early 1980s were dashed when Denktash proclaimed an independent “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” — an entity recognized only by Turkey to date.

Open conflict loomed in the 1990s when the Greek Cypriot government considered purchasing a Russian-made S-300 missile defense system — a move quickly dropped when Turkey threatened military action.

Repeated failures of diplomacy and the accompanying rhetoric of ethnic nationalism have taught political analysts to manage their expectations.

“Recent electoral results in northern Cyprus have strengthened hardliners there — and they are themselves benefiting from Erdogan’s material and ideological support,” Tsarouhas told Arab News. “For the first time, Turkish Cypriots now claim that a two-state solution is the only way forward, and Erdogan echoes that. This means the partition of the island.

“On the other hand, it is equally true that Greek Cypriots have missed their opportunities to push for a successful resolution of the problem in the past, so they are not in a hurry. They have never been, since 1974.”

Stavros Avgoustides, ambassador of Cyprus to Saudi Arabia, rejects the claim that the Greek Cypriot side has also mishandled the issue and places the blame squarely on Turkey.

“The failure of successive efforts to achieve a solution was fundamentally due to Turkey’s insistence to maintain Cyprus as a protectorate through the obsolete post-colonial system of guarantees and the presence of Turkish troops on Cyprus’ soil,” Avgoustides told Arab News.

“Cyprus has ended up being ‘ethnically divided’ as a result of the 1974 Turkish military invasion and occupation and the policy of ethnic cleansing executed by Turkey against the people of Cyprus.”

Judging by the statements coming from Ankara, it is obvious that ruling party politicians have nothing to lose by adopting a harder line ahead of the UN-led meeting. “There is no longer any solution but a two-state solution,” Erdogan told a meeting of his Justice and Development Party (AKP) last week. “Whether you accept it or not, there is no federation anymore.”

A day later, in an interview with TRT Haber, Ibrahim Kalin, the presidential spokesman, expanded on his boss’s statement. “We cannot discuss the things we discussed for 40 years for another 40 years,” he said.

“Now, this issue will be discussed under the UN’s roof. It will be discussed at the 5+1 talks. We will now be discussing a two-state solution.”

The remarks by Erdogan and Kalin came shortly after Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the Greek prime minister of Greece, said that “significant” talks to reunify Cyprus could not be resumed if Turkey insists on a two-state accord that disregards the UN and EU framework for a peace deal.

Even if next month’s meeting goes ahead as planned, a successful outcome is far from guaranteed. After all, with the new millennium had come renewed impetus to resolve the dispute, led by Annan. The 2002 road map — known as the Annan Plan — envisaged a federation with two constituent parts, presided over by a rotating presidency.

If the Greek and Turkish Cypriot sides agreed to the plan, Cyprus was to be offered EU membership. If they failed, only the internationally recognized Greek Cypriot south would be permitted to join.

The Annan Plan was put to the Cypriot public in twin referendums in 2004. Although it won support among Turkish Cypriots, it was overwhelmingly rejected by Greek Cypriots, thus compounding the situation.

Animosity between the two sides deepened in 2011 when Cyprus began exploratory drilling for oil and gas. Turkey responded the following year with its own drilling onshore in northern Cyprus despite protests from the Cypriot government. In a parallel development, UN-sponsored reunification talks launched in 2015 again ended inconclusively in July 2017.

Then, in Oct. 2020, anti-reunification nationalist Ersin Tatar narrowly won the Turkish Cypriot presidency, making the UN-backed vision for peace seem even more unviable. With the Turkish side backing Ankara’s demand for a two-state formula, expectations of a deal based on the UN resolutions being reached are low.

As far as the Greek Cypriots are concerned, the terms have not changed, according to Ambassador Avgoustides. “We are committed to the continuation of negotiations with the aim of achieving a solution of a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation as provided in the relevant UN resolutions,” he told Arab News.

“We earnestly hope that the same level of commitment will be displayed by all involved.”

A solution must “fully respect the basic rights and fundamental freedoms of all Cypriots, that will free Cyprus from foreign guarantors and from the presence of foreign troops, and will render it fully able to exercise its role as a beacon of peace and stability in the eastern Mediterranean.”

As things stand, whether the two competing visions for the future of Cyprus can be reconciled in the near future is an open question.